ASL Didn’t Fail—We Failed to Apply It With the Commitment It Deserves

One of the most painful things I see—as an audiologist, interpreter, and someone who grew up signing—is when parents say, “We tried ASL, but it didn’t work.” Or, “We put them in a class with an interpreter, but they didn’t catch up.”

But that’s not a failure of the language. It’s a failure of implementation. And more often than not, it’s a failure of access.

ASL isn’t a hobby. It’s not like trying out gymnastics or learning to watercolor. It’s a full language system—one that takes years of consistent, immersive input to become fluent. And when it is taken seriously, it changes lives.

I know this personally. My very first exposure to ASL wasn’t through school—it was through the Deaf daughter of a neighbor. That little girl had significant disabilities, and her parents were told to institutionalize her. They were told she would never learn language. That she would never function.

But they didn’t listen.

Hearing is Non-Binary

What I’m advocating for is expanding the conversation around deafness to include sensory-based auditory barriers, especially in educational and workplace settings.

This isn’t about appropriating Deaf culture or identity. It’s about recognizing that hearing is not binary. Many people—particularly APD, ANSD, and autistic individuals—may “pass” a hearing test but still struggle profoundly to process, tolerate, or make use of sound in real-world environments. That lived experience deserves recognition, accommodation, and language access.

Using tools like ASL isn’t about claiming Deaf identity—it’s about reducing communication deprivation. Just as audiobooks and captions have expanded access without erasing their roots in disability culture, ASL can serve broader access needs without diminishing its cultural integrity. Respecting Deaf culture and using ASL as a tool for survival and inclusion are not mutually exclusive.

The Risks of Poor Programming for Low-Gain Hearing Aids

Poorly programmed LGHAs can deliver output levels above 130 dB (per Phonak), which is well into the danger zone for noise-induced hearing loss. In some cases, overamplification has led to long-term sound sensitivity, tinnitus, and even hearing damage—especially in children.

On the other end of the spectrum, under amplification or poor physical fitting can be just as harmful. Early in my career, I worked under a supervisor who fit a young child with a mild hearing loss and clear signs of sound hypersensitivity. Instead of supporting his access to meaningful sound, she fit him with hearing aids that had completely occluding earmolds—no venting at all—and programmed them with such low gain that virtually no useful sound got through.

The result? His ears were physically sealed off from the outside world, but not meaningfully supported. The combination of blocked canals and minimal amplification created an unnatural, echoey, and overly silent soundscape—essentially placing him in a sensory deprivation chamber.

He didn’t just lose access to high frequencies or soft speech—he lost access to the foundational sounds of language itself. His hypersensitivity to sound wasn’t addressed; it was amplified through isolation.

Top 12 Spatial Hearing Activities for Kids (and Playful Adults)

Hearing challenges are one of the most overlooked causes of academic struggles in both children and adults. When we think of hearing loss, we often picture someone with a visible hearing aid or a significant audiogram shift—but many students who struggle in school have invisible hearing difficulties that never get flagged as “hearing loss.”

Some children miss key sound information because of auditory processing disorder (APD), where the brain struggles to organize and interpret sounds correctly—especially in noisy environments. Others may have dyslexia, which is often tied to reduced access to phonological information and poor speech-in-noise processing. Some experience fluctuating or unilateral hearing loss that makes it hard to localize sound or follow group discussions. And many children with auditory sensitivities or sensory processing differences find sound overwhelming, inconsistent, or painful—leading to shutdowns or avoidance in learning settings.

In all of these cases, one of the biggest hidden challenges is spatial hearing—the ability to figure out where a sound is coming from, how far away it is, or who’s speaking in a group. When spatial hearing is weak, the world feels unpredictable. The child may seem inattentive, anxious, or overwhelmed—not because they’re not trying, but because they can’t anchor themselves in space through sound.

The good news? Spatial hearing can be nurtured through play.

The following activities are movement-based, curiosity-driven, and often involve vision-restricted listening to help sharpen attention and sound mapping. Many of them work just as well for teens or adults as they do for kids. Because they include movement and navigation, safety and supervision are essential—but so is creativity. Pull out your scooter pads, a helmet, a blindfold, and a sense of adventure. These aren’t just games—they’re tools for rewiring the way the brain interacts with sound.

Here are 12 of my favorite activities to build spatial listening skills—for kids, teens, and playful adults alike:

Self-Guided Auditory Training for Adults with Sensory Sensitivities

For adults, especially those who are neurodivergent or sensitive to sensory input, structured clinical tasks can feel artificial or overwhelming. But when you embed auditory training into real-life, personally meaningful environments, the brain becomes more willing to engage and adapt. Here are some ways adults can guide their own auditory development through intentional, real-world practice…

Look Me in the Eye: Proving Auditory Processing Disorder Is Physiologically Real (and Should Be Included in DHH)

One of the biggest challenges with auditory processing disorder (APD) is that we’re still stuck treating it like a behavioral or educational issue—not a medical one.

The standardized tests we use to diagnose APD are entirely behavioral. A child is asked to repeat words in noise, track tones, or follow verbal instructions. These are functional, yes—but they rely heavily on attention, language, and task performance. So when a child struggles, it’s easy for people to assume the issue is attention, motivation, or learning—not how their brain is actually processing sound.

And to make matters worse, there is no gold standard for APD testing.

The batteries vary wildly from clinic to clinic, subtracting even more credibility from the diagnosis in the eyes of schools, insurance companies, and even other clinicians.

When Flexibility Isn’t a Gift: How Ehlers-Danlos Can Disrupt the Auditory System

When people think of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), they usually picture joint hypermobility, stretchy skin, and chronic pain. But one of the lesser-known impacts of EDS is how it can affect the auditory system—and not just in ways that show up on a standard hearing test.

We tend to treat hearing like it’s binary. You either have hearing loss, or you don’t. But for many people with EDS, especially children, their audiogram looks fine—yet they’re clearly struggling. They might complain of sensitivity to sound, fatigue in noisy environments, difficulty keeping up with verbal instruction, or frequent misunderstandings. And when they do, those symptoms are often brushed off as behavioral, attention-related, or emotional. In reality, their auditory system just isn’t working the way it’s supposed to.

Hearing depends on a delicate system of pressure regulation, mechanical movement, and reflexive protection. That means the eardrum has to vibrate with just the right tension. The ossicles—the tiny bones in the middle ear—need to move efficiently, with stable joints and well-tuned ligaments. And the acoustic reflex, which helps dampen loud noises, needs to fire quickly and reliably to protect the cochlea and brain from overstimulation. But in EDS, connective tissue doesn’t behave normally. The ligaments can be too lax, the membranes too stretchy, and the reflexes too inconsistent.

It’s like trying to control a marionette puppet with strings made of soft, unpredictable elastic. One day, everything looks normal. The next, the whole puppet collapses. The movement is inconsistent, the signal is unstable, and when that happens in the ear, what reaches the brain is already degraded.

“Dyslexia doesn’t suddenly appear in third grade.” So why do we often wait until then to intervene?

This blog post explains how dyslexia, auditory and visual processing disorders, hearing loss, and language delays often overlap—and why early, layered intervention is critical. It also introduces a growing referral network of professionals working together to ensure kids get the right support, without unnecessary testing or barriers to care.

Speech Sounds You Can See

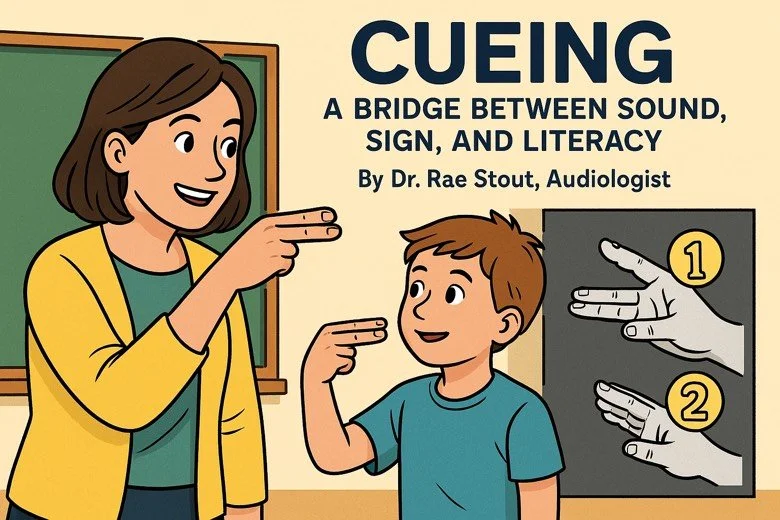

When a child struggles to hear clearly, speak confidently, or read fluently, we often treat the symptoms separately—speech therapy for articulation, reading intervention for decoding, and hearing aids for audibility. But there’s a quiet gap running underneath all three: a gap in phonological access. For many children with auditory processing disorder (APD), auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD), peripheral hearing loss, or even normal hearing with dyslexia, the problem isn’t just hearing sounds—it’s recognizing, sequencing, and storing them accurately. That’s where cueing becomes transformative.

Cueing is a visual system that represents the individual phonemes of spoken language using a combination of handshapes and placements near the face, in sync with natural mouth movements. There are just eight handshapes for consonants and four placements for vowels, but when combined with lipreading, they give a child full access to every spoken sound in the language. It’s not about teaching a child to speak—it’s about giving them access to the structure of language itself. The smallest units. The ones with meaning.

Why Is My Child Strong in Expressive Language, Yet Weak in Receptive?

One particular child I worked with stood out. He could monologue for long stretches about specific topics—space, engines, the periodic table—and used expressive language that seemed incredibly mature. But he often insisted on controlling the conversation. His parents said he would redirect or interrupt if they tried to discuss anything outside of his preferred interests. He would often become frustrated or shut down if a conversation shifted away from a familiar script.

Interestingly, his parents didn’t believe he was autistic. They saw him as quirky and highly verbal—but also emotionally intense, sometimes sensitive to sound, and occasionally rigid in his routines. When I tested him for auditory processing difficulties, it quickly became clear that he was missing a great deal of incoming language, especially when it was rapid, abstract, or layered with background noise. It wasn’t that he didn’t care what others were saying—it was that he simply couldn’t track it unless it matched something he had already internalized.